Rosemary’s Baby, the second film in the Apartment Trilogy and arguably one of Roman Polanski’s best directorial efforts, is drawn from Ira Levin’s novel. Levin took his own anxiety about impending fatherhood and crafted an engrossing and darkly comic story about young New Yorkers becoming parents to Satan’s child. When Paramount producer Robert Evans acquired the rights he sent the novel to Polanski assuming the Holocaust survivor would have a unique perspective on evil.[1] He was right. “I don’t have a relationship to evil,” Polanski said in a 1999 interview. “I’ve never believed in occultism or the Devil, and I’m not at all religious. I’d rather read science books than something about occultism. When it comes to cinema, evil is simply a form of entertainment to me.”[2] Taking its place among the greatest horror films ever made, critic Rich Cohen credits Rosemary’s Baby with giving birth to a genre that includes The Omen and The Exorcist. “It now seems less like horror, more like social commentary,” he writes. “It’s not about the devil and it’s not about madness. It’s about men and women and when they do to each other. It’s our world in microcosm – that’s the curse. It says more than it wants to. In the way of great art, it captures a beast it did not know it was hunting.”[3]

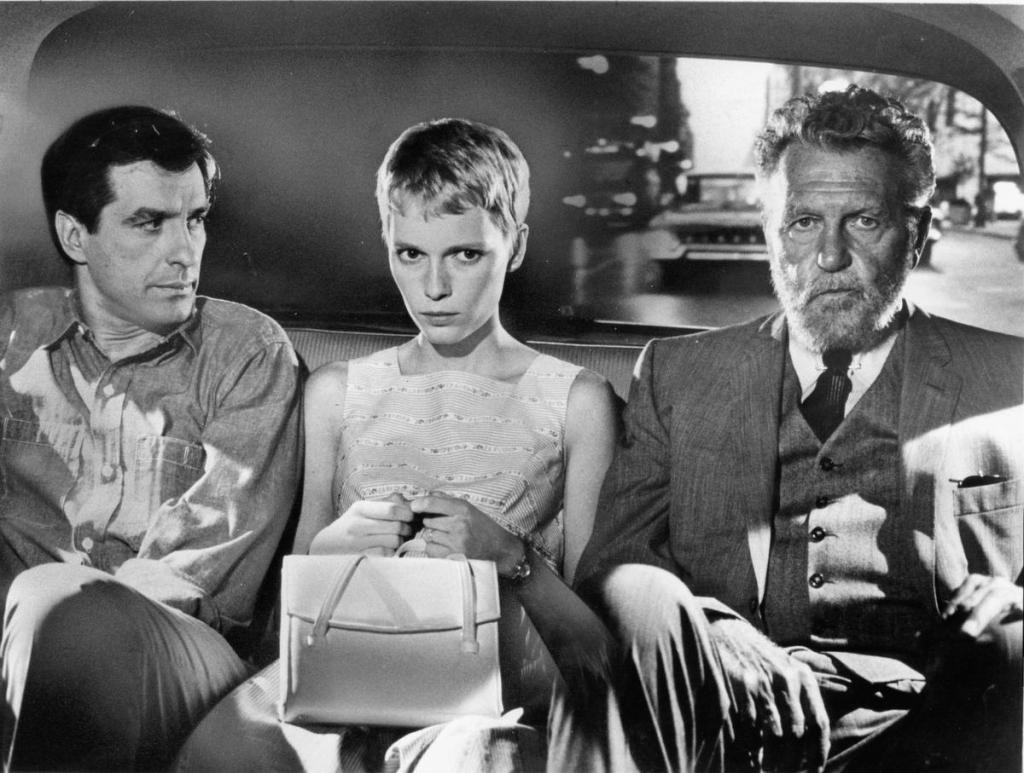

The film begins with Rosemary and Guy Woodhouse (Mia Farrow and John Cassavetes) moving into the Bramford, a Manhattan apartment building with a colorful past, namely cannibalism, murder and witchcraft. The ambitious and artistic couple soon meet their elderly and eccentric neighbors, Minnie and Roman Castevet (Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer). Rosemary befriends Terry (Victoria Vetri), a young woman and recovering drug addict living with the Castevets, but Terry soon hurls herself out of a seventh-floor window to her death (a theme in the trilogy). Once Minnie learns Rosemary and Guy are trying to get pregnant, the Castevets take an active interest in their lives, securing for them an exclusive doctor, providing Rosemary a tannis root “good luck” charm, and preparing special drinks and meals infused with herbal supplements. As Guy struggles to make it big as an actor, Rosemary is left isolated in the increasingly menacing and strange apartment and forced to accommodate Minnie’s incessant meddling. In an abrupt turnaround, Guy welcomes Minnie and Roman’s friendship and begins landing lucrative acting jobs. One night, Rosemary has a horrifying nightmare about being raped by the Devil on John F. Kennedy’s yacht, but the next morning Guy assures her he simply had sex with her in her sleep to keep their schedule. Now pregnant, Rosemary experiences months of pain and disorientation while the Castevets become more intrusive than ever. Hutch (Maurice Evans), a family friend who warned Rosemary about moving into the troubled Bramford apartment building, urges Rosemary to abandon the regimen prescribed by the Castevets and their doctor, Abe Sapirstein (Ralph Bellamy). Hutch begins investigating the Castevets and discovers their long history with the occult and satanism, but he falls into a coma before he can reach Rosemary. When Hutch dies Rosemary comes into possession of his research and discerns the truth about the Bramford, the Castevets, and her pregnancy. The Castevets and Sapirstein are part of a coven, and Guy made a pact with the Devil in exchange for fame and fortune. At first Rosemary believes the witches want her child for evil purposes, but the film concludes with the horrible realization that her son Adrian is the son of Satan. With the coven assembled in the Castevets’ apartment, Rosemary warily approaches her demonic son in his black bassinet and cradles him, smiling.

The genius of Rosemary’s Baby is that, like the protagonists in Repulsion and The Tenant, we are watching a woman’s slow descent into insanity, but this time the Rosemary’s fears seem warranted. As Rosemary cries out during her surrealist rape by the Devil, “This is no dream. This is really happening!”[4] Everyone from her husband, the annoying neighbors, to the kindly old Dr. Sapirstein seem to have Rosemary’s best interests at heart, yet an immense conspiracy envelops the hapless young woman to the point she loses her mind. We believe her, but the rest of the world either dismisses Rosemary as a hysterical woman or is in on the Satanic plot. Every time she tries to leave the apartment and seek help Rosemary is dragged back to the sanctum to perform her only role, birthing Satan’s son. The horror in this iconic film unfolds slowly and from unexpected quarters. The only overt sign of monstrosity are the piercing yellow eyes of Rosemary’s rapist, the Devil himself. Although we do not see Adrian, Roman assures Rosemary, “he has his father’s eyes.”[5] Rosemary is suffocated by the apartment, her duplicitous husband, the neighbors, male doctors who are accustomed to compliant female patients, and society’s timeless expectations concerning what constitutes maternal behavior, as evidenced by the film’s ambiguous conclusion. “Rather than fight the oppressive rule of her captors,” Nick Yarborough writes, Rosemary “appears to have finally surrendered—content to be a prisoner of the apartment if it means being with her baby—consequences be damned.”[6] While Damien “The Omen” ascends to the top of the socio-political hierarchy simply by maneuvering existing institutions, reinforcing the patriarchal foundation of the civilization he will conquer, Rosemary is a disposable pawn used by the patriarchy to perform one function – birth the Antichrist. “Whatever happened to Rosemary’s baby?” audiences asked in the years after the film’s release. Perhaps The Omen trilogy is an answer.

As in most of Polanski’s work, Rosemary’s Baby does not reference the Holocaust or antisemitic imagery directly, but the film features “Jewish” characters and characteristics. Minnie and Roman’s personality and mannerisms, particularly Minnie’s passive aggressive nudging of Rosemary throughout the pregnancy are coded as Jewish. Sapirstein is an authoritative and avuncular doctor resembling a more rotund Sigmund Freud. Furthermore, the cabal is engaged in a vast conspiracy involving witchcraft and the theft of children. After receiving Hutch’s research, Rosemary’s eyes widen reading about coven rituals in which an infant’s blood is drained. The manuscript is reminiscent of the infamous blood libel accusations plaguing Jews since the medieval era. Polanski plays with the stereotypes not to inflame passions, but to achieve a comical affect. That a coven of eccentric yentas and octogenarian professionals can hatch such a conspiracy in the comfort of their living room is absurd, yet strangely convincing, especially from Rosemary’s admittedly frantic perspective.

The most unsettling aspect of the film is not that Rosemary is victimized by Satanists, but that she surrenders, that she is complicit. We also cannot dismiss the idea that the entire episode is in fact a hallucination. When interviewers observed Polanski’s characters are “always helpless at the end of your films,” the director replied that showing your hero triumphant “leaves the audience satisfied. And there’s nothing more sterile than the state of satisfaction.”[vii] Perhaps by necessity given his experience as both a victim and perpetrator, Roman Polanski observes the world through an absurdist lens, and from a distance. “I’m interested in what makes you tick,” Charlie Rose said, pressing Polanski to reveal more in an interview. “I know you are,” Polanski replied curtly, “But I’m not.”[viii]

[1] Rich Cohen, “‘Rosemary’s Baby’ 50 Years Later,” Wall Street Journal, May 23, 2018.

[2] Cronin, 175.

[3] Cohen.

[4] Rosemary’s Baby, directed by Roman Polanski (1968: Criterion Collection), DVD.

[5] Rosemary’s Baby, DVD.

[6] Yarborough.

[vii] Cronin, 44.

[viii] Cronin, 188.